|

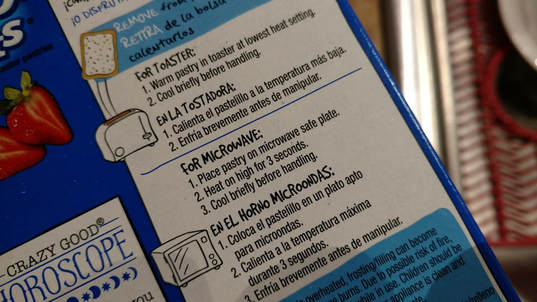

Me: Oh, sweet! You only need three seconds to warm up a pop tart in the microwave! Narrator: He would need more than three seconds to warm up a pop tart in the microwave.

0 Comments

I studied rhetoric and composition/writing studies at the University of Texas at El Paso. Early in my coursework, as does every student, I came face to face with the question "what is 'rhetoric'?" I joke that the way most people use the word "rhetoric" they mean something like "lying." So when I tell people I have a PhD in "Rhetoric," I wonder what they think. The exceptions to this assumption, I have found, are theologians and lawyers who understand the nature of rhetoric historically and as part of their fields. I'll leave you to your own counsel about whether rhetoric-as-lying still applies in their cases as well...

Midway through my PhD coursework, I slowly began to wonder if rhetoric as a field of academic study had any substantive content of its own or if it was simply "parasitic" on other fields. I was relieved to know this was a common concern and that the field did indeed have answers to the question what does rhetoric provide as a matter of substance. As my research and study took me into the sub-field of "technical communication" the sense of what it is I independently as a researcher and scholar provide returned, though somewhat muted. This question is fraught with implications from the personal to the social and cultural as well as the political (the value of the humanities is perennially the subject of derision among politicians). So it's one that recurs occasionally. Recently, while revisiting Angela Haas's 2012 article "Race, Rhetoric and Technology" I found myself chasing down citations in her bibliography in more depth than I had before. There Joseph Jeyaraj's 2004 JBTC article "Liminality and Othering" caught my attention. Here he makes the case that "technical writers" are "liminal subjects" (p. 15). He summarizes Turner's (1974) definition of "liminality" as that "state of flux that emerges at a particular stage in the temporal process of a community" (p. 15). He also builds on Gaonkar's argument "that all rhetorical knowledge is characteristically liminal" (p. 16). For Jeyraj, rhetoric "as a liminal discipline, is able to freely interact with the discursive practices of different disciplines so that new ideas and fresh knowledge of these discursive practices may emerge" (p. 17). This article resonated so fully and suddenly anew because I've been recently wrestling personally and professionally with being a "liminal" person, someone who has always found himself inhabiting "in between" spaces, physically, socially, culturally, intellectually. I suffer with bouts of insecurity (as I imagine everyone does at one time or another) about what it is I do. Academic research is very much about pushing out past the boundaries of what is known and accepted so you often find yourself trying to think and write things with very few people around you, conceptually--perhaps only a few luminaries pointing the way, equally lonely themselves. As a profession it simply exacerbates our natural anxieties circulating around meaning in our lives. I suspect also that this question lingers because we value the concrete, the material, that which can be built and "cited" more quickly. But as Jeyraj and others have noted, the liminal work of rhetoric--or really any kind of "translation" work, be it conceptual or linguistic, is extraordinarily valuable. At least, that is what keeps me working day to day... |

Beau Pihlaja, PhDExploring our global connections. Archives

October 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed